Species ecology in thermal landscapes

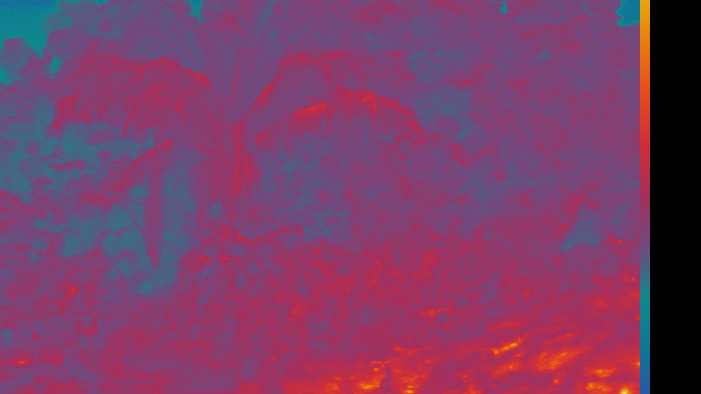

Thermal image of a forest-pasture edge

Thermal image of a forest-pasture edge

The big idea underlying our thermal landscape work is that species-specific traits like tolerance to high temperatures, or thermal preferences, play a major role in determining how amphibians and reptiles respond to landscape and climate change. We often think of landscape change, like deforestation, as altering resource availability, or changing the strength of biotic interactions among species. While those things are true, deforestation also replaces relatively cool and thermally stable forest with relatively warm but thermally variable types of land cover. For ectothermic species, whose body temperature largely correlates with air temperature, changes in the thermal landscape resulting from deforestation can be profound. The consequences of changing thermal landscapes can be especially problematic for tropical species that are adapted to a narrow range of relatively constant temperatures. Species that occur exclusively or mostly in forest often cannot ‘take the heat’ in warmer parts of the landscape.

Our thermal landscape work often combines field, lab, and geospatial modeling approaches. We typically collect amphibians and reptiles while using standardized sampling methods to describe patterns of density and distribution in the field. Those animals are then used in non-lethal lab trials to determine species traits like high temperature tolerance (CTmax) or thermal preferences. We also monitor temperatures in the field using data loggers and thermal images.

Some of the insights we have gained as a result of our thermal ecology work are:

• High temperature tolerance strongly predicts responses of tropical amphibians and reptiles to habitat modification and fragmentation.

• Species with high temperature tolerance persist in small forest fragments or non-forested parts of the landscape, whereas species that cannot tolerate high temperatures are limited to large forest patches.

• Thermal tolerance mediates edge effects for tropical amphibians and reptiles.

• Sensitive species occur further from forest edges than species with higher thermal tolerance.

• Thermally sensitive species may be filtered from what are currently suitable vegetation types as climate changes.

• One species of tropical frog switches habitats as temperatures change along an elevation gradient.

• The species is restricted to forest in the warm lowlands, but tracks its preferred temperature into agricultural clearings at cooler, higher elevations.

• Density of a thermally-sensitive species of tropical salamander appears to be declining in warm, low-elevation portions of its range.

• Density is negatively correlated with temperature along the elevational gradient, and contemporary populations at one site are less than half what they were 10 years previously.